A Conversation with Elena Karina Canavier

On August 5, 1979, the following conversation (which has been edited) was recorded by David Schaff, poet and art critic, at Elena Karina's home in Washington D.C., as she was preparing for an exhibition at the Everson Museum of Art.

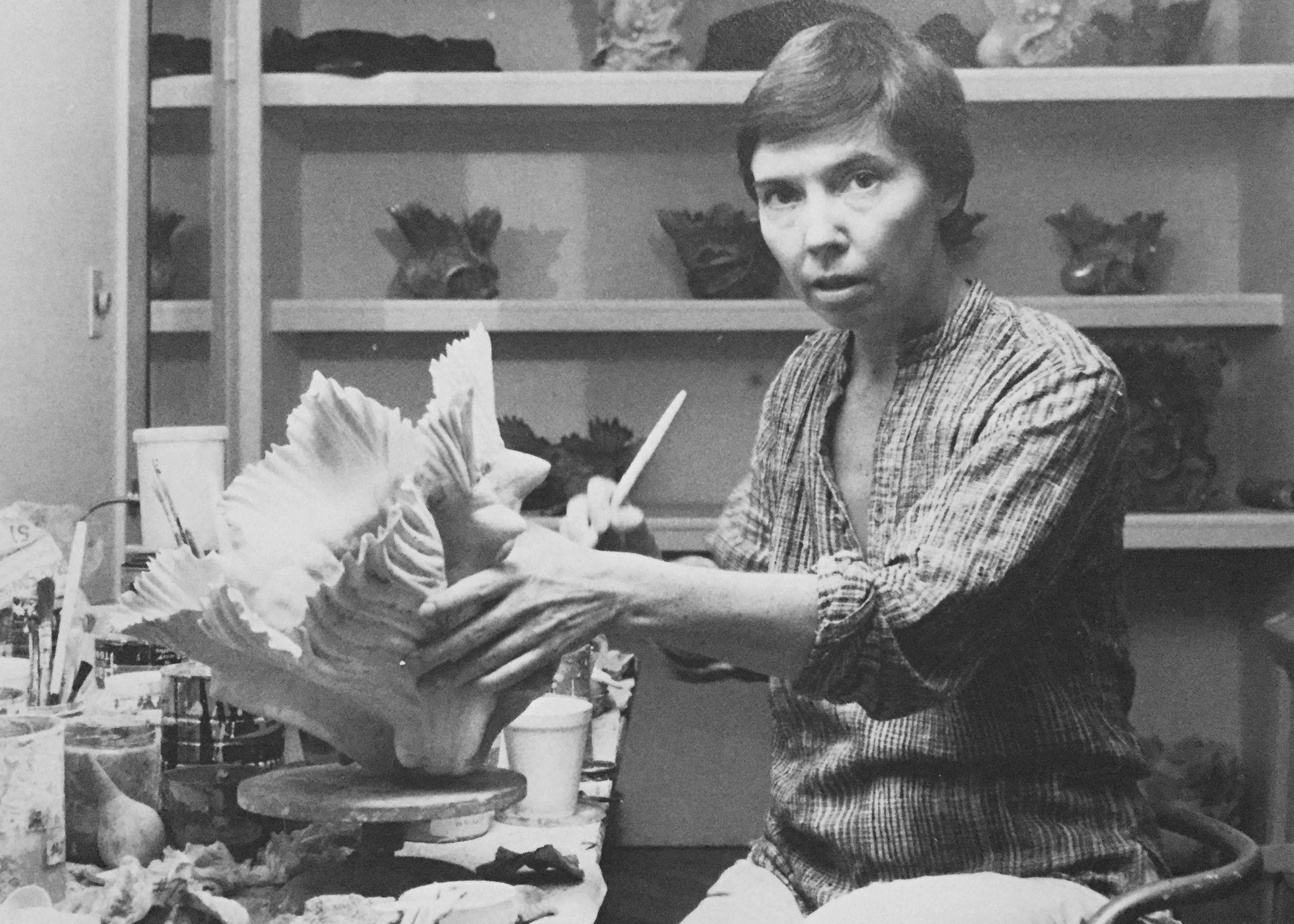

Elena Karina in studio, 1979

D.S. — Since the mid-60's, you have created three series of works in clay: large sculptures of closed, stacked forms; sculptured vases on cast aluminum bases; and the most recent - the smaller porcelain vessels, like the ones you are exhibiting at the Everson Museum, which you sometimes call "tide pools." How did these "tide pool" vessels develop and when did you begin to do them?

E.K. — The "tide pool" series emerged as a really identifiable, full-blown form around 1968. I mean that is the point in time when I came to certain formal decisions; for example, the relationship of the base to the rim; the commitment to hollow, open form, and so forth... also, by that time I was honing in on the right glazes and claybodies for these forms. Actually, I had been working toward this imagery since about 1957... but so many extraneous possibilities had to be weeded out, before I felt that I had something solid... a definable area staked out. As it turns out, this "tide pool" form has continued to fascinate me... I keep finding new aspects to develop and to push further... but, of course, in 1968, I had no idea that it would be such a fertile area for me!

D.S. — Did the large works - the stacked sculptures and the sculptural ceramic and metal vase forms - immediately preceed the "tide pool" series?

E.K. — Yes. Although, I did many small vessels from 1957 to the mid-60's, that I now see were prototypical of the "tide pools," they weren't really complete statements... and the large sculptures, made between 1963... and 1967 were much more serious, considered pieces. But they were just so slow to make, and physically exhausting... and very heavy, I couldn't move them by myself. So the decision to work smaller again was a relief - it gave me much greater control over the medium and the whole process. The feedback from one piece to the next came much faster... I could try more things... and from that point the development was quite rapid.

D.S. — The feeling of marine life is strong in your work, but why do you call these forms "tide pools"? I don't think I know what a tide pool is.

E.K. — Well, as you know I'm from California... and the beaches there, some fo them are very rocky; well, during low tide, when the surf recedes, you can see pools of water trapped by rock ledges and in these pools you can see sea anemones, shells, baby fish and crabs, scallops, all kinds of things. During the 60's, I had my studio near a beach like this... and I did a lot of walking and looking. So at the time when I was evolving the imagery, I'd think of the inside of the vessel as looking down into the pool and seeing the swirling, splashing water... and the outside as the dry shale cliffs by the beach, the barnacles and shells, the lichen... but basically, the name "tide pool" stayed because I needed to name this form. It is not a utilitarian form, it doesn't exist as a class of things: I mean, I can't call these things "tureens" or "ash trays" or "chairs" because they are not. So the term "tide pool" kind of stuck because these forms are, in a sense, a new class of object really, and they need a name.

D.S. — The marine reference or inspiration then is not really a direct one any longer?

E.K. — Actually, the pieces are self-referential... each new piece is derived from the preceding one. I am really interested in the manipulation of certain shapes - which I think of as my alphabet - it's a kind of vocabulary of shapes I have built up: the the clusters of cones, the fan shapes, the bulbous pearl, crescents... I like to play with them, to combine and recombine them... pushing a certain gesture until I have pushed it as far as it will go. The pieces in the Everson show titled Swan I, Swan II, Swan III, and Swan IV, are an example of pushing a certain gesture - a kind of springing out from the base.

D.S. — I notice that you have titled some of the pieces in the Everson Museum exhibition with the names of painters: Botticelli, for example, and Boccioni... how does this relate to "tide pools"?

E.K. — Well, don't you think that all names are, in a sense, rather arbitrary labels of convenience? They facilitate identification. I refer to all these vessel forms I have made in the last few years as "tide pools" because then I know which forms we are talking about. But when we want to talk about a specific piece... I need to have a name, a title to conjure it up in my mind. It's hard to remember which piece is "I.D. number 4-11-79," for example, but if someone tells me they like the piece called Boccioni, or Swan I, I know immediately which piece they mean. I make the pieces first and the title comes later. Each piece has a definite character, so I try to choose a name that fits. It's like adopting a kitten... you probably let it wander around the house for a few days before you name it.

D.S. — Your new series of porcelain vessel "tide pool" forms show a distinct change of palette from the 1974 series - which were quite dark, with more greens, deep browns, and slate grays... the new ones are so delicate and much lighter toned...

E.K. — The palette change really does reflect an unconscious process. I guess it's the artistic process. Maybe it's peculiar to painters. The physical environment always finds a way to surface, visually, in my art. The other day, I stood back and looked at all the pieces lined up, ready to go up to the Everson - and I realized with a shock that those colors are what I see in downtown Washington every day: granite grays, marble and stone, pale concrete pavements, slate... Washington is basically a light gray city... with a touch of pink from the bricks, and sometimes at sunset.

D.S. — How do you get the build-up of color, the delicacy of color range?

E.K. — The glazing is a very painterly process for me. I apply the glazes with a brush, so it's really painting on an irregular, three-dimensional surface. And I fire in an oxidation atmosphere in an electric kiln... so that I have almost total control of what happens in the kiln. I don't rely on accident.

D.S. — So you are not involved in that wonderful process in which one puts glaze on the piece, starts the kiln, and then takes the work out hours later in a state of amazement.

E.K. — Yes and no. That's a wonderful experience. But you have to be careful. Ceramics is very much like printmaking. The etching press and the silk screen can bring so many rich qualities to a print; the kiln and glazes can do the same for ceramics. But at some point, it becomes important to acknowledge the possibilities of the medium and then ignore those that are not in service of the kind of image you want to achieve.

D.S. — I am sure that people must ask you "How do you make those pieces?"... they are outstanding virtuoso accomplishments, simply on the level of skill.

E.K. — Yes, a lot of people ask me that question... and I feel that many of them ask it because it gives them time to look at the work., a kind of stall, a buffer while they try to asses their feelings about the work... But i don' go into explanations of the precise technique. I feel it would be a diversion away from the confrontation with the image. And anyway, I think that art should be magical.

D.S. — During your Southern California years, were there any painters tor ceramicists with whom you felt particular affinities?

E.K. — Well, I think it may help, when you see the almost baroque quality of my work, to understand that I did stidy with Rico Lebrun at the Jepson Art Institute. Even though I never really assimilated the Lebrun Style, I did admire his draughtsmanship and chiaroscuro.

D.S. — a very maximal imagery...

E.K. — But other than the art school period, I can't say there were any affinities... quite the contrary, most often I found myself in opposition, in my artwork, to the prevailing mode - this was especially true in the area of ceramics.

D.S. — Do you feel any particular affinities with other periods in sculpture in which similar typesd of formal, iconographic values were important?

E.K. — Yes I do. But in a general way. There's a rather complex layering of associations. One is a very strong bond with the whole history of ceramics - It is important for me to feel that I am making objects that would be admired in just about any period or any culture in the past that had developed an appreciation for ceramics as a high art... that's also a strong motivation for my choosing the vessel format - even though these pieces are not utilitarian, the hollow vessel as a concept, or form, makes my work a link in an unbroken tradition... going all the way back to pre-history.